Burgundy and the Central Coast

When a New World winemaker claims to make a “Burgundian wine,” it is really an impossible statement. So many differences separate Burgundy and California that you cannot really compare the two regions. A Burgundian wine carries the name because it was produced from within the rich environment of Burgundy, France, where vines have developed for centuries to interact ideally with every possible environmental factor.

The climates of California and Burgundy differ from each other in many ways. For example, the vineyards in Burgundy experience three weeks of snow every winter whereas California’s grapes grow in a largely Mediterranean environment. In Burgundy, one would not see vegetation that thrives in many California wine regions, such as avocado trees. Another difference between California and Burgundy includes the length of the growing season: in the summer, Burgundian vineyards enjoy a good 2.5 hours more sunlight a day than California’s vineyards.

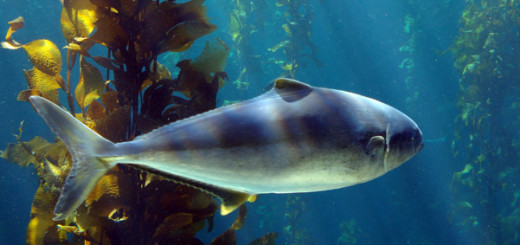

Edna Valley, looking north toward Islay Peak

So many other factors differentiate Burgundian wines from those produced in the new world. For example, vines in Burgundy are planted closer together than in places like Argentina and the US, due in part to limited availability of land. Burgundy’s poor soils and tight vine spacing result in lower yields than many other wine producing regions around the world, contributing to a concentration of flavors in the finished wine. Another area of difference is in that Californians battle mildew issues while Burgundian growers face the challenge of Botrytis. Also, in California the fruit generally has a higher pH and lower acidity than in Burgundy. So, rather than suggest that it’s possible to make a “Burgundian wine” in California, I draw inspiration from this great region and lean toward making Burgundian-influenced California Pinot Noirs.

California Has No Terroir, Yet

I get very cautious when people start talking about terroir in California, as it’s really not possible to apply the concept of terroir here as the French understand it. In France, terroir emerges from the complete integration and sustainability of working from vine to wine within one region and the definition and determination of the absolute best way to work with the varietal in this particular environment over many years. Terroir is so much more than the simple combination of a varietal, the earth, and the climate: it is a complete refining and polishing of how to work with the vine in every way.

The best practices developed for French vineyards have been applied, in the case of some Grand Crus, for hundreds of years. The vines adapt and change significantly as they grow in an area for a long period of time. When replanting at a traditional vineyard in Burgundy, one may graft a cutting of vegetal material from the current vineyard to the rootstock. This vegetal material has been perfectly “stabilized” for and is indigenous to and endemic of this one area. One may also use cuttings from other neighboring vineyards in the same region. The new world has no such “genetic library” of vines as has France. Only through such a library can one begin to really study terroir in the finished wine.

Many viticultural elements continue to undergo change in California wine country, as well as in other new world wine regions. It is impossible at this time to say that a region has finalized everything there is to know about the terroir of a wine region. I know it’s very sexy to talk about terroir in the US and other new world wine regions. However, one cannot actually determine the best way to grow anything if one consistently changes variables in the vineyard such as trellises and canopy management practices, as happens throughout these regions on a regular basis. For example, in the Edna Valley and Arroyo Grande Valley of Central California, practices and vines have changed dramatically even in the last 15 years. One can only begin to identify the terroir of a vineyard after a particular piece of land has hosted particular vines planted in a particular way for many years, perhaps several hundred.

Steps Toward Terroir

We are taking “baby steps” toward developing a real sense of terroir in the new world. Trial and error eventually leads to success. Here’s an example of a lesson learned: for years we planted vines in an east-west orientation to assist the creeping fog into the vineyard from the ocean, just a few miles to the west. Unfortunately, this orientation caused the grapes on the southern exposure to ripen well while the grapes on the northern side of the vine couldn’t ever quite ripen properly. The sun’s effect trumped any perceived benefit for the fog in achieving the balanced ripening of the fruit, which is such a key factor with successful Pinot Noir. We learned from this experience, and have repositioned the vines.

While I don’t believe that today California wines truly demonstrate terroir in the French understanding of the term, we know the potential is there. I know that new world wine regions hold the future promise of their own, genuine sense of terroir after they’ve evolved and approached perfection over many more vintages. There is so much more to discover. In fact, it was this sense of discovery that drew me away from my native Burgundy and toward the new world 20 years ago. Growing up in a traditional village in Burgundy, I soon realized there was not nearly as much to discover as a winemaker at home as there was in the new world. New world winemakers enjoy more freedom and increased opportunities for creativity.

A Burgundian Style

The wine style embraced by winemakers and consumers in any historical period reflects current society. A dramatic shift in styles occurred with Burgundian Pinot Noir in the early nineteenth century. Prior to 1820, most of the wine produced from this grape in Burgundy consisted of delicate rosés. Wine styles continued to evolve and change over time. By the early 1900s, Pinot Noir in Burgundy was being made into big, rich, and concentrated wines. In the 1960s and 1970s, this wine became considerably lighter and fruiter again. As in the fashion industry where a fresh collection is unveiled each year, new wine styles sometimes demonstrate a subtle evolution from the previous approach to crafting a particular wine while, at other times, the changes in a particular wine style differs dramatically from its previous style.

I draw much inspiration from Burgundy when making Baileyana Pinot Noir. My wines generally have lower alcohol and brighter acidity than most California Pinot Noirs. They are rich with red cherry, raspberry, black cherry, and soft plum flavors. Well balanced and elegant, these wines pair nicely with a wide range of foods.

Pinot Noir: The Perfect Food Wine

Pinot Noir is a very versatile food wine because of its high acidity and rather low tannins. Some of the best food pairings with Pinot Noir include the following:

- Grilled seafood steaks with garlic or tomato-based sauces

- Roasted poultry with fruit-based sauces

- A cheese plate of Edam, Gouda, Gruyere, and Saint Andre

Christian Roguenant, originally from Burgundy, is the winemaker for Baileyana Winery and Tangent Winery in the Edna Valley AVA

This article first appeared on colorandaroma.com

photos: Baileyana Winery