Jerry Garcia, the Dead and My Winemaking

by Wes Hagen, Clos Pepe Vineyards

When asked to pen an article about Jerry Garcia and wine, I will admit that I wasn’t immediately hooked on the idea. The two subjects seemed incongruous. Hippies drink $2 Heinekens or $1 Domestics in the parking lot if they drink at all, or at least that’s what I remember from the innumerable parking lot scenes that I wandered semi-aimlessly while following the Dead for a while. But the parking lot scene at a Dead show has little to do with who Jerry Garcia was and what the Dead was about. As I began to make an outline for this article, I was actually surprised how easily I could make connections between Jerry and my own ideas of wine, music, craft and doing something that makes people high and happy.

![]()

So let’s get down to it: How did Jerry Garcia influence my winemaking?

“Don’t panic, it’s organic.”

Wes delivers a rapid fire geological history of the Santa Rita Hills

I won’t tell you what the hippie barker was selling with that repeated mantra, but I suspect it wasn’t USDA inspected. His voice still rings in my head, though—a representation of that doe-eyed belief that we could all live in peace and eat food free from pesticides and corporate taint. Today, I have a very balanced view of conventional and sustainable agriculture but still have a strong bent toward using methods that respect the product I craft: Pinot Noir from one of the most beautiful pieces of dirt in the New World. A hippie adolescence provided me both an education in environmentalism as well as a healthy curiosity and skepticism that keeps me from drinking the biodynamic Kool Aid or joining Earth First.

So Jerry brought me to the Dead, the Dead brought me to the parking lot, the lot taught me to love the Earth but it also taught me to be skeptical of the lot. My first show, Anaheim Dead/Dylan in 1987, disenchanted me because I felt that hippies were two-faced—anti-capitalist drivel rolling out of one side of their mouths while they hawked veggie burritos out of the other. Of course, not all hippies are driven by the dollar and now there’s corporate veggie burritos. Isn’t it cool how philosophies seek the middle ground as time marches on?

Understand the Past to Move into the Future

During the first of my 52 Grateful Dead shows, Jerry sang a folksy little song I had never heard on Skeletons from the Closet or American Beauty. It seemed the whole crowd knew the lyrics but me—I felt like an American atheist at his first High Mass in Rome. Everyone else knew when to sway, sing, kneel, chant and respond to the ritual being performed. “What song is this?” I yelled to the Wookiee to my left. “Jack-a-Roe!” he replied between fits of bone shaking. “Is it an original?” I asked, bothering him again. Instantly becoming more erudite than stoned, he began my schooling: “It’s an eighteenth century whaling song—traditional, you know?” So there I was in 1987 at a rock concert, listening to a whaling song from the 1700s, surrounded by people stuck somewhere between the Age of Enlightenment and the Age of Aquarius.

some tickets from Wes’s 52 Dead shows

The Dead could never be defined as a rock band. They were part folk, part bluegrass, part jazz, part rock, add one part liquid LSD, a few shots of whiskey for Pigpen, and an audience stretched to schizophrenic passion for every note that emanated from the Wall of Sound. The entire band loved music with an abandon that informed them and allowed them to stretch their music into forms that have still not evolved in other musical genres. Jerry was a nine-fingered jug-band banjo-plucker who settled for an electric guitar. Bobby Weir was a beautiful, long haired hippie who loved to sing Elvis songs. Phil Lesh was a legit classical musician out of the celebrated Berkeley Academy of Music. Billy Kreutzman was a jazz drummer who laid down complex rhythms that drove the music forward in unexpected ways. Pigpen was a hard drinking blues singer and harp player. Together, they made a sound that was purely unique and as American as jazz.

For me, wine and music are about passion, personality and place. East Coast shows were different than West Coast shows like Burgundy is different than Santa Barbara Pinot Noir. Musical terroir, perhaps? But the point of this section is that understanding the history and traditions of your craft, music or wine (or both!) will allow you to benefit from the centuries of successes and failures of making vintages or melodies. In that moment when the audience expects brilliance, the past speaks through us—if we are literate—through the earth and through those who have touched us as artists or teachers. Without tall and strong shoulders to stand upon, we cannot see “Furthur.”

Complex but Elegant

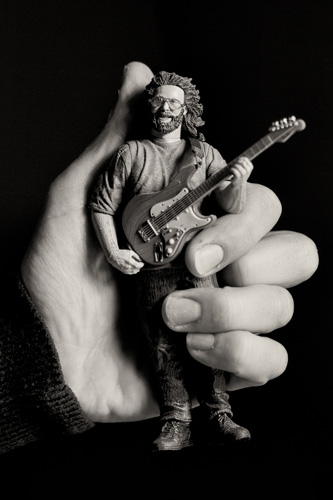

mini Jerry

Throughout his life, Jerry Garcia considered himself a musical charlatan. He humbly told many of his closest friends that he didn’t consider himself a great guitarist and was constantly amazed that people continued to line up to see him play. His first words as he came out of his first diabetic coma: “I’m no Beethoven.” The mathematic definition of the word “elegant” is “simplicity.” I believe the power of Jerry’s playing was an amazing ability to reinvent melodies into new melodies that had not been complicated in the process. It’s like seeing Monet’s work in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. You look at it and believe it’s so simple, so universal, that you could have—no, you SHOULD have painted it. That’s what I call Universal Artistic Simplicity. The work speaks so clearly and purely because it is raw and unadorned humanity.

The wine version of this concept is winemaking that attempts to showcase climate and soil over winemaking affectation. It’s Chablis-style over butter-and-oak. Elegance over ripeness; restraint over concentration. Any kid can learn how to tap out a heavy metal scale, just like any winemaker can let their Cabernet ripen to thirty brix. But try to imitate Jerry Garcia’s solo in a 1971 Stella Blue—or try to make San Joaquin Grenache taste like a 1971 Trapet Chappelle-Chambertin—and you’ll quickly learn the lesson. Greatness emanates from where passion meets nature’s capacity to support that dream. With the Dead, on a steam-train-rolling kind of night, the instruments combined to form something immediately complex but also simple. With wine, I have to resort to a more musical language to explain: “Il vino es la poesia della terra.” Wine is the poetry of the earth.

Clos Pepe in the Santa Rita Hills, Santa Barbara County

When in Doubt, Ride the Wave

No memoir on Grateful Dead music is complete without a story of shamanistic ritual, psychedelic abandon, and (with any luck) a return to sanity that drives home some hidden universal truth. Unfortunately, I was never that cool or crazy. As far as you know. But I did have an epiphany of sorts watching “the Boys” one fine evening in October 1989 in Mountain View, California. As I closed my eyes to concentrate on the music (and not the tall hippie in front of me who danced as if he were humping an imaginary sheep in front of him), I saw the whole band, sans Jerry, creating this beautiful blue wave of music—wave crashing, wave rising, wave falling, wave moving, building, waning—and Jerry was riding the wave. The melody was Garcia’s board and it was there to keep him from falling. But, like any good surfer, he wandered to every edge he could carve and explored it, ripped it, made it cry, and then brought it back to the center of the board before being sucked into the tube and ejected in a glorious burst of musical mist supplied by the rest of the band.

OK, so that was a little weird. If you followed that stream-of-hippie speak, you probably went to more shows than I did. Now where were we? Oh yeah, wine! So the best way to be a great winemaker is to be a great viticulturist. If you can grow your own fruit, then you truly are a wine maker. Extending the metaphor, the climate is the wave (the band), the terroir is the board (the melody), and the farmer/winemaker is Jerry—exploring the quality and the breadth of the potential (vintage) and the craft (manipulations/soloing).

2000 Pinot Noir, Wes’s first vintage

So, while Jerry’s job was to put sparkle on top of a solid musical foundation behind him, my job as a winegrower is to maximize the uniqueness of vintage by custom tuning my cultural practices (farming the vineyard) to make quality fruit that makes great wine. If frost comes, we turn on the wind machines and sprinklers: “Wind and rain…tell me why, seasons will end and roses die….” We pull leaves from the fruit zone to increase air movement in the canopy to reduce vegetal aromas and improve high-toned fruit character: “Sunshine daydream, meet me in the tall trees, going where the wind goes….” In music, wine and life the best we can do is to ride the wave with passion and aplomb.

In the End, It’s Slightly Meaningless

Oscar Wilde says in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray “All art is quite useless.” Considering Wilde’s formidable intellect and erudition, I can’t disagree with him before I agree with him. Would the world be dark and bereft without the music of Jerry Garcia and the taste of wine? Hell no! We would have beer and tequila and whisky and whiskey; we would have Hendrix and Coltrane and Mozart. Compared to our relationships and our passions, wine and Jerry are meaningless in a Buddhist all-is-transitory sort of way. But (apologies to Oscar and his lily-toting fanboys) my world would be much different and far less rich without the addition of Jerry’s bubbling guitar (the whaling tunes and all) and wine’s poetic expression of fruit and earth. It’s only wine, but I have dedicated my life and passion to it. It’s only music, but Jerry plays the way I wish I could play.

The Summer of 1995 was a sad year for Deadheads: Jerry died. That year my life changed: I left the teaching profession to go full time into winegrowing. It’s been fifteen years and I love this vineyard, my Deadhead wife, and the shrine to Jerry on our mantle. We still listen to the music almost every day—in fact my wife says we can only listen to Grateful Dead and Bob Marley when making our estate wines. Hmm…Bob Marley’s influence on winemakers: a subject for another article, perhaps?

![]()

Wes Hagen is Vineyard Manager-Winemaker for Clos Pepe Vineyards and Estate Wines in the Santa Rita Hills as well as a writer, wine consultant, and wine educator

photos: Jeremy Ball of Bottle Branding