Reality Cooks and TV Dinners

For me, watching a chef cook feels like taking a tranquilizer: cooking shows are a happy pill to counteract the crazy in the world. True, Food Network stars like Ina Garten on “Back to Basics” and Tyler Florence on “Tyler’s Ultimate” have to get a lot done in a half hour, but they are practiced at it and good at making it look easy. For the ultimate spa treatment of culinary entertainment, I tune into what PBS serves up. The public broadcasting station offers a relaxing, commercial-free zone, so nothing unpleasant intrudes as Jacques Pépin whips, folds, dices, and sautés through “Fast Food My Way.”

When I want more than a spa experience, I turn to competitive cooking shows for their intensity. Competitive cooking shows remind me of watching a horse race with the jockey wielding a spatula and whisk instead of a crop. The tasks are timed and, at the end of a single show, the judges decide on a winner.

“Chopped” on the Food Network is one of these shows and it’s the only one I can’t bear to watch. With 20-minute time constraints and strange combinations of ingredients in the mystery baskets, the show reminds me of a boot camp for circus performers. “And for my next act, I will take this can of anchovies, a bag of cotton candy, a dragon fruit, and cheddar cheese and create a 5-star dessert in less than 30 minutes.” The chefs are paraded in front of the dour-faced judges after each of three rounds and one judge will say something like, “Your use of poppy instead of sesame seed and the fact that you deep fried your cheese just didn’t work and for that reason we had to chop you.” The show has crossed the line from dramatic to ridiculous, and for that reason I had to chop it.

“Chopped” on the Food Network is one of these shows and it’s the only one I can’t bear to watch. With 20-minute time constraints and strange combinations of ingredients in the mystery baskets, the show reminds me of a boot camp for circus performers. “And for my next act, I will take this can of anchovies, a bag of cotton candy, a dragon fruit, and cheddar cheese and create a 5-star dessert in less than 30 minutes.” The chefs are paraded in front of the dour-faced judges after each of three rounds and one judge will say something like, “Your use of poppy instead of sesame seed and the fact that you deep fried your cheese just didn’t work and for that reason we had to chop you.” The show has crossed the line from dramatic to ridiculous, and for that reason I had to chop it.

The media mind who devised the combination reality show/competitive cooking show should get a Nobel Prize for entertainment. These shows capture the excitement of old-time Saturday matinee serials. My mother told me about them: every Saturday, she watched on the big screen as Buck Rogers faced danger and death. She wondered and worried all week about how he could possibly escape. Finally, Saturday would arrive and Buck would prove to be invincible once again, only to be thrown from the frying pan back into the fire. The delicious anticipation of finding out how he would survive kept her trolling alleys for bottles to exchange for enough pennies to see the next flick.

The media mind who devised the combination reality show/competitive cooking show should get a Nobel Prize for entertainment. These shows capture the excitement of old-time Saturday matinee serials. My mother told me about them: every Saturday, she watched on the big screen as Buck Rogers faced danger and death. She wondered and worried all week about how he could possibly escape. Finally, Saturday would arrive and Buck would prove to be invincible once again, only to be thrown from the frying pan back into the fire. The delicious anticipation of finding out how he would survive kept her trolling alleys for bottles to exchange for enough pennies to see the next flick.

I find the anticipation extra delicious when the drama unfolds in the kitchens of the Top Chef catalogue of shows on Bravo TV and the Next Food Network Star on the Food Network. The formula of reality show—the month-long isolation from family, the exile from all that is familiar, and the close quarters with strangers combined with continual challenges and pressure—is like a crucible for the soul. Dross is skimmed off and refined metals remain. Or, to put it in culinary terms, it’s like rendering fat. This transformation of characters is what I find so fascinating. Not only is the alchemy in the mixture of ingredients served up each week for the judges, but it is also within the psyche of the chefs. The recipe compels each character to change. I end up caring about the people, feeling like I know them, and sad to see them lose and “pack up their knives and go.” I admit there are some chefs who I’m glad to see go because they annoy me or I don’t like the way they do their hair. Like the petty, harsh world of junior high school, it’s quite satisfying.

In the finale of Top Chef Just Desserts, the winner was Yigit Pura, a first-generation Turkish-American and the first gay man to win a Top Chef competition (ain’t that America!). He was supposed to be an economics major and make his money in business, but his heart was in the kitchen not the boardroom. His dad told him to “live from your heart” and it’s that passion I see week after week in all the chefs. Most are expats from other professions; often, they were musicians. Most know they are doing exactly what they were meant to do. Some are just finding their stride. Each week, I watch as they dig deeper than they thought they could and refine their craft until, win or lose, they stand taller.

Chefs are sometimes tripped up by their own personalities. This is most evident in the Next Food Network Star where contestants are often home cooks, not professional chefs. Some chefs are overconfident: I’m going to win, no doubt, I’m the best. These folks usually don’t win. At the other end of the spectrum are the chefs who hold back and seem unsure: I don’t know if I can do it but I’ll try. These usually don’t do it. In between are those who say I’ll just do my best, cook my food, that’s all I can do. They usually make it to the final contests. Those who win Top Chef honors or become the Next Food Network Star really do believe in themselves. Some have discovered this during the show, and some knew it to begin with. The defining characteristic of the winners is not simply the absence of self-doubt but the existence of self-belief.

Chefs are sometimes tripped up by their own personalities. This is most evident in the Next Food Network Star where contestants are often home cooks, not professional chefs. Some chefs are overconfident: I’m going to win, no doubt, I’m the best. These folks usually don’t win. At the other end of the spectrum are the chefs who hold back and seem unsure: I don’t know if I can do it but I’ll try. These usually don’t do it. In between are those who say I’ll just do my best, cook my food, that’s all I can do. They usually make it to the final contests. Those who win Top Chef honors or become the Next Food Network Star really do believe in themselves. Some have discovered this during the show, and some knew it to begin with. The defining characteristic of the winners is not simply the absence of self-doubt but the existence of self-belief.

Top Chef Masters and The Next Iron Chef (Food Network) rate high on my TV menu. These shows feature chefs who are the best in their fields. The chefs don’t live together so there is less of the personal drama seen in reality shows and more emphasis on cooking. These are the soufflé of cooking shows, whereas the others are more like county fair food. There’s a place for both in any balanced diet.

Top Chef Masters and The Next Iron Chef (Food Network) rate high on my TV menu. These shows feature chefs who are the best in their fields. The chefs don’t live together so there is less of the personal drama seen in reality shows and more emphasis on cooking. These are the soufflé of cooking shows, whereas the others are more like county fair food. There’s a place for both in any balanced diet.

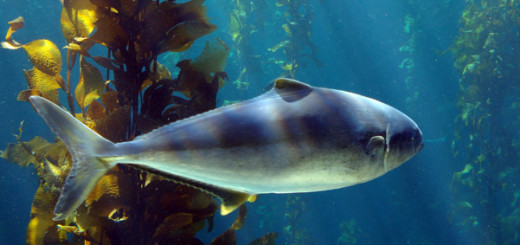

Just as it’s bad for the digestion to eat right before bedtime, I’ve found that watching competitive cooking shows in real time, usually at 9 or 10 at night, is bad for my sleep. When I was a novice watcher, I’d lie awake in bed until 2 a.m. conjuring dishes in my mind: how I would have approached the challenge, what I would have made with cabbage, trout, and quail eggs, how I would have spiced the dish differently? I’ve learned to record the shows and watch them earlier so I have time for imagining and devising well before bedtime.

Just as it’s bad for the digestion to eat right before bedtime, I’ve found that watching competitive cooking shows in real time, usually at 9 or 10 at night, is bad for my sleep. When I was a novice watcher, I’d lie awake in bed until 2 a.m. conjuring dishes in my mind: how I would have approached the challenge, what I would have made with cabbage, trout, and quail eggs, how I would have spiced the dish differently? I’ve learned to record the shows and watch them earlier so I have time for imagining and devising well before bedtime.

With so many shows now airing, I have lots of inspiration for thinking up dishes, and all that deep thought has found its outlet in my kitchen. I’ve been inspired to refine my own cooking skills and develop new recipes. Last year, I stepped into the competitive arena and submitted three recipes to a sandwich recipe contest. After six months of experimentation, during which my husband enjoyed being my official taste tester, I sent them off to be judged. I knew I had done my best and that was all I could do. When I didn’t win I was let down and a bit miffed, but I got over it. I had a taste of what the “chef-testants” go through every week. Like them, I cleaned off my cutting board, sharpened my knives, and kept cooking. I may not have won, but there was nothing lost either. My husband still raves about my Pizza Panini, and in the words of Ina Garten, “How bad can that be?”

Margaret Lange is a poet, writer, and singer/songwriter who is at the tail end of completing her first CD. She founded the Sky World Poetry Series, hosted “The Spoken Word” on Excellent Radio, and taught poetry in the schools with California Poets in the Schools. She lives in a rural town on the Central Coast of California where she can often be found in her kitchen fiddling with food.

The Origins of the Cooking Show by Kathleen Collins

Garten photo: Quentin Bacon