Wine and Treachery

We experience so many pleasurable moments with wine—pairing it well to a fine meal with friends, raising a toast to a new venture, closing our eyes with enjoyment as a delicious taste swirls on the palate—it’s easy to forget that wine has also channelled many a darker purpose. A relatively recent and high profile deceit with wine involved the (very expensive) sale at Christie’s of Bordeaux bottles allegedly belonging to Thomas Jefferson. These bottles, engraved with Jefferson’s initials, drew intense attention from wine lovers who couldn’t afford them and those who could.

At auction, a member of the wealthy Forbes family bought one bottle for $157,000 while William Koch paid a cool half a million for four bottles of wine sporting the initials of our third US president and most famous early American wine aficionado. Four bottles of wine for $500,000! Koch is the titular billionaire in Benjamin Wallace’s The Billionaire’s Vinegar (2009), which details how human beings, no matter how wealthy, share the same tendency to believe (for a while, at least) what they want to believe. Until they learn that the initials “Th.J” on the bottle were engraved with power tools not yet developed in 1787.

The Jefferson Bottles: How could one collector find so much rare fine wine?

by Patrick Radden Keefe, The New Yorker, September 3, 2007

Veddy Unfortunate: How the greatest wine hoax ever has diminished a brilliant British oenophile by Mike Steinberger, Slate.com, August 18, 2009

What is it about wine that makes it the perfect liquid on which to float devious plans? Is wine more prone to treachery because of its inherent intoxicating quality that reduces one’s inhibitions? When wine plays a narrative role in human stories, it often serves as a delicious conduit to evil.

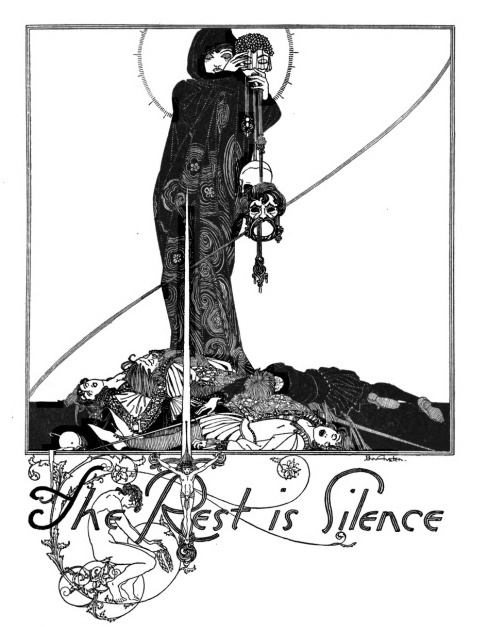

Consider Queen Gertrude of Shakespeare’s Hamlet: while attempting to toast her beloved yet estranged son, Gertrude unknowingly drinks from a poisoned cup of wine designed to kill Hamlet, should the poisoned sword of Laertes fail to kill him first. Drinking heartily of the wine intended for her son, she says “The queen carouses to thy fortune, Hamlet.” King Claudius tries to stop her: “Gertrude, do not drink,” which she meets with her challenging response, “I will, my lord; I pray you, pardon me.” A few lines later, Gertrude collapses to the stage floor, the first in what will be a pile of dead bodies in that final bloody scene. “How does the queen?” Hamlet asks as Claudius tries to hide his own treachery: “She swoons to see them bleed.” With her last breath, she blames both the wine and the king: “No, no, the drink, the drink,–O my dear Hamlet,–The drink, the drink! I am poison’d.” [Dies] With water too transparent that it might reveal the king’s treachery, wine provides cover for poison. Characters in such narratives can’t help themselves from draining a delicious glass of wine, even if it provides a vessel for death.

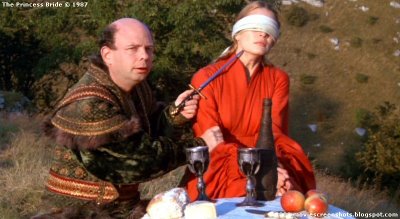

one of my favorite movies!

From the sublime to the ridiculous: the wine in The Princess Bride (1987) that Vizzini sets out for the Dread Pirate Roberts on a rustic table becomes the weapon in a battle of wits. The choice of beverage is significant: not water, not milk, but wine. “To the death!”

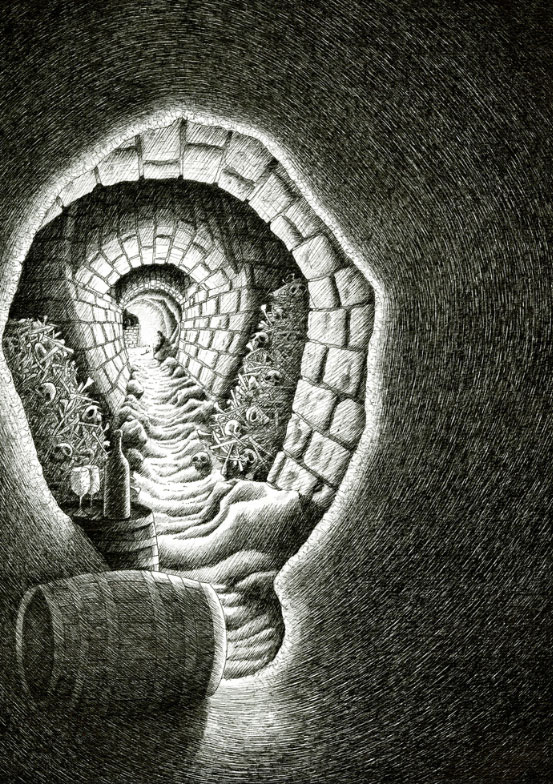

Wine as a conduit for treachery infuses Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Cask of Amontillado.” This story has it all: the outsized ego associated with “knowing” good wine, the willingness to delve deep into a musty cellar for a sublime taste, drunkenness, and death.

If you do drink wine, to avoid treachery, be sure to let down your guard only with true friends. ; )

Shakespeare illustration: John Austen

Poe illustration: Phill Myatt